The development of low-carbon hydrogen is taking a growing place in the debates on energy transition. With 96% of the world’s production currently based on fossil fuels, can hydrogen play a role in decarbonizing the economy? Europe’s electricity mix is also giving an increasing place to intermittent renewable energies, and hydrogen is being studied as a potential lever for flexibility to ensure the security of electricity supply. On November 13th, Think Smartgrids organized a web conference to take stock of this new technology and its potential, through different use cases, as well as the challenges of developing low-carbon hydrogen for networks and energy transition.

Guillaume DUSSAUX, Business developer for hydrogen project at ABB, and Etienne BRIERE, R&D Program Director on RE, Hydrogen, Storage and Environment at EDF R&D, recalled France’s main quantified objectives concerning the reduction of emissions and the production of decarbonated hydrogen. Thus, the National Low Carbon Strategy sets the objective of a 40% reduction in greenhouse gases (GHG) by 2030 compared to 1990, yet the 920,000 tons of “grey” hydrogen used each year by France represents about 3% of the country’s CO2 emissions. The stakes are high for decarbonizing activities such as oil refining, fertilizer production and chemicals, but also for heavy mobility, especially ships.

If we follow the objectives set by the Multiannual Energy Program (MEP), by 2035, 630,000 tons of decarbonated hydrogen should be produced annually, which would require the use of a little less than 5% of the nuclear and renewable electricity produced in France. Ten Power-to-Gas demonstrators should thus be launched by 2023 before large-scale deployment ; 6.5 GW of electrolysers would also have to be installed by 2030 to decarbonize the industry. In addition, there are projects to develop hydrogen for transport (road, rail, waterway), the objectives of which have been set by the Hydrogen Plan adopted in 2018 by the French government. In 10 years, the plan calls for the deployment of at least 20,000 light commercial vehicles, 800 heavy vehicles (buses, trucks, regional trains, boats) and 400 hydrogen stations.

ABB has thus already worked on various use cases, in particular to decarbonize industry and ships. The Hybrit project in Sweden, for example, aims to produce steel with zero CO2 emissions by replacing coal with hydrogen and electrifying the processes, while FLAGSHIPS is testing the economic viability of maritime transport based on shore-based electrolytic hydrogen production and fuel cells. The Delfzijl project in the Netherlands has launched a 20 MW electrolyser producing 3000 t of hydrogen per year to produce green methanol, partly for use in aircraft. The objective is to save 27,000 t of CO2 per year, with an eventual ramp-up to 60 MW.

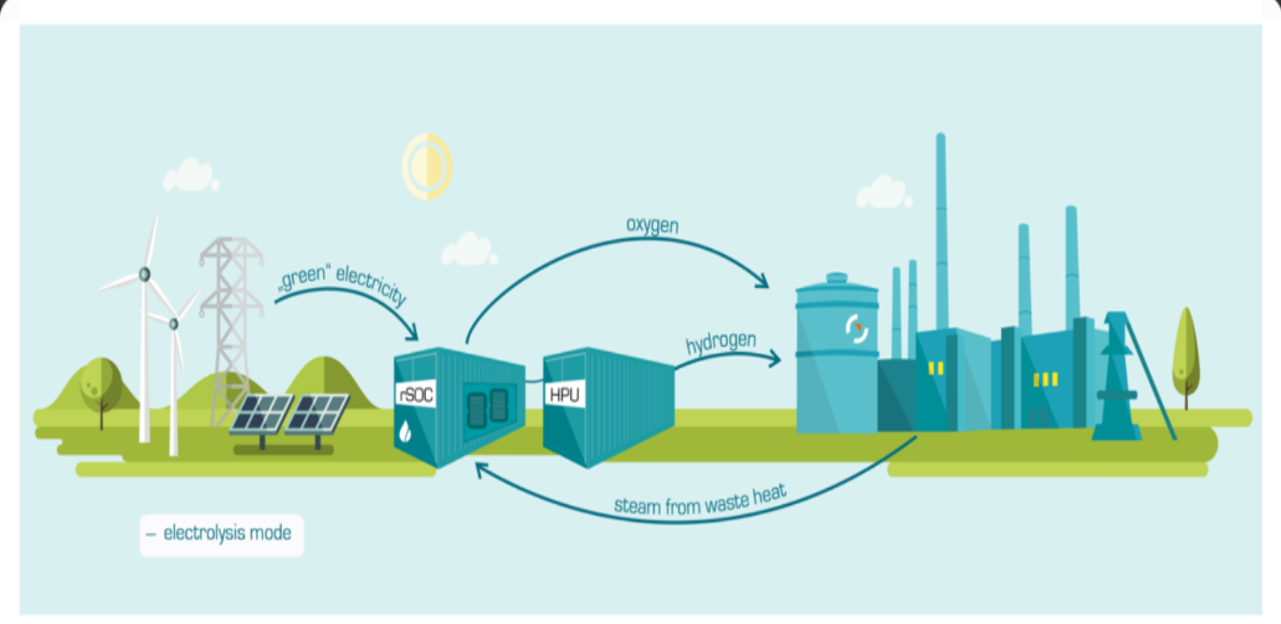

For networks, hydrogen is also being studied for its possible contribution to the supply/demand balance and flexibility, in the face of the sharp increase in the share of intermittent renewable energies in the electricity mix and the growth of new uses such as the electric vehicle. According to Guillaume Dussaux, the aim is not only to electrify, but also to automate and digitize hydrogen production by electrolysis to make it controllable and integrate it into the overall electrical system, with the important issue of the cost of this energy in mind.

As Etienne Brière reminds us, in addition to the question of cost, there is also the question of the energy efficiency of the production of this “green” hydrogen, as well as that of the transport and storage of “the lightest gas in the Universe”. EDF R&D has thus focused its priorities on the decarbonization of industry and heavy mobility, with the overall efficiency of the “power to H2 to power” process being only 30 to 35%, with the cost of the electricity produced being at least 10 to 20 times higher than electricity from the French grid, and storage presenting strong technical constraints.

EDF has been working since the 1970s on the development of electrolyzers. Two years ago, the French utility launched its subsidiary Hynamics to invest, develop and operate electrolytic systems in order to market decarbonated hydrogen. Etienne Brière explains that the main challenge, at a time when the sector is developing rapidly, is now to move from projects of a few megawatts (MW) to scales of several tens or even hundreds of MW of production capacity, with the search for high-performance business models. In Germany, for example, Hynamics is working on a 30 MW electrolyser project to decarbonize oil refining, which aims to increase to 700 MW by 2030, hoping to achieve significant economies of scale.

Indeed, Etienne Brière reminds us that producing and marketing hydrogen requires much more than electrolyzers. A lot of power electronics is needed for the power supply, but also hydrogen purification systems and compressors. Fixed costs are therefore important, and low-carbon hydrogen will not find its economic model before developing larger production capacities. Thus, EDF does not envisage for the moment developing electrolysis as a means of storing surplus renewable energy, whereas the cost of hydrogen is today much higher than that of methane.

On the other hand, the EDF group is working on various projects to decarbonize the steel industry, to develop hydrogen for buses and trucks, or for microgrids. Its international R&D center EIFER, based in Germany, and the EDF Lab Les Renardières, in Seine-et-Marne, are also conducting numerous experiments on low-carbon hydrogen.

But hydrogen also opens up new prospects for the energy transition of certain regions. Jonathan Morice, Director of Climate, Environment, Water and Biodiversity for the Regional Council of Brittany, recalled that Brittany, a peninsular region with no nuclear power plant, adopted an “Electricity Pact” 10 years ago to strengthen the network, reduce energy consumption and massively integrate renewable energies into the network, taking advantage of the region’s maritime character and its high potential for the development of marine energies.

These are all reasons that led the region to adopt an ambitious roadmap for the development of hydrogen last July, after consultation with some 200 local players and with the support of Bretagne Développement Innovation, a key player in Brittany’s energy transition.

Brittany has focused its priorities on land transport, especially heavy transport, which is difficult to convert to electricity because of the high autonomy and power it requires. The ports could also have a significant impact on the development of the hydrogen market, as the volumes ordered to power large ships with hydrogen would be significant.

Offshore wind power is seen as one of the major levers for producing this electrolytic hydrogen, but Brittany is also considering production from biogas, relying in particular on its agricultural sector.

The Hydrogen Roadmap 2030 thus aims to develop 3 axes:

- The parallel development of uses and infrastructures, via calls for projects for public-private partnerships.

- Strong support for R&D

- Giving visibility to the players, with a major structuring plan for collective investments

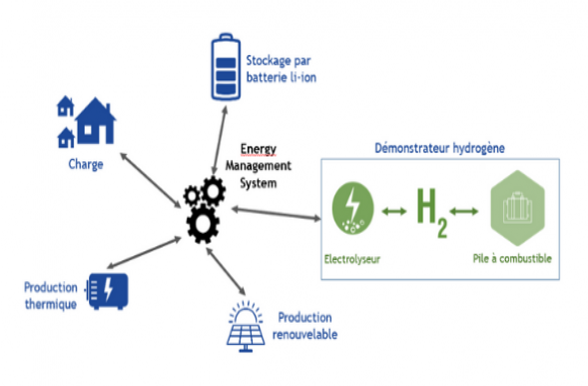

Among the first 8 projects already deployed in Brittany, Jonathan Morice cites the example of the island of Molène, a Non Interconnected Area (NIA) where all electricity is currently produced by a thermal power plant, while the French Multiannual Energy Plan is aiming for 70% RE in the electricity mix by 2028 for these areas isolated from the continental grid. In addition to energy efficiency measures and the deployment of RE, storage and control systems will be essential to achieve this objective. In addition to lithium-ion batteries, hydrogen will be used to overcome the constraint of inter-seasonal storage. Several projects for hydrogen-powered boats are also underway.

Last month, the region launched the call for projects (AAP) “Renewable Hydrogen Territorial Loops” , which is due to close on November 20th. Others will follow, in 2021 and 2022.

Despite major obstacles in terms of production, logistics and storage costs, low-carbon hydrogen offers very interesting avenues for decarbonizing industry and heavy mobility in particular. Major efforts are being made by the French industry, both in terms of R&D and to find viable business models. The latter will above all require a scaling up to make high investment costs profitable and an optimization of operating costs, which will notably involve the digitalization of operations. However, the hydrogen market seems to be well on the way to creating industrial ecosystems in Europe, having managed to carve out a prominent place for itself in the French, German and European recovery plans. The future will tell us whether the results are equal to the ambitions.